Introduction: The Ubiquitous Icon Born from Serendipity

Post-it Notes have become an indispensable and iconic tool, so deeply ingrained in daily life that their ubiquitous presence in offices, homes, and classrooms worldwide is often taken for granted. These small, colorful squares function as silent workhorses of organization and communication, a testament to their simple yet profound utility. This humble product has, over decades, achieved a nearly mythic stature in consumer culture, symbolizing quick notes, efficient reminders, and streamlined organization.

The remarkable story of Post-it Notes is a compelling narrative of innovation born not from direct intention or a pre-identified market need, but from what has been widely described as a “happy accident” and a “solution without a problem” that serendipitously stumbled upon its true purpose. This brand story stands as a powerful testament to how persistence, collaborative ingenuity, and a unique corporate culture can transform an overlooked scientific discovery into a global phenomenon.

The narrative of “accidental innovation” is central to the enduring appeal of the Post-it Note brand. This particular framing humanizes the brand’s origin, making it inherently relatable and inspiring for a broad audience. It suggests that groundbreaking ideas do not always follow a linear, predictable path or emerge solely from deliberate, targeted research efforts. Instead, the Post-it Note’s genesis champions the idea that innovation can arise from the most unexpected places, and that apparent “failures” or deviations from initial goals can, in fact, be crucial stepping stones to unforeseen and monumental successes. This perspective also subtly challenges the traditional notion of the “lone genius inventor” by highlighting the pivotal role of serendipity and subsequent collaborative effort.

The Genesis of a Gentle Grip: Spencer Silver’s “Solution Without a Problem”

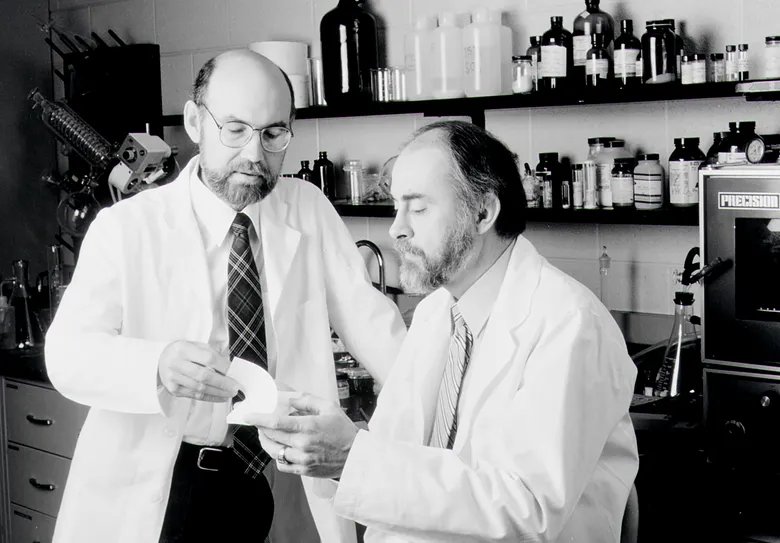

The genesis of the Post-it Note brand traces back to 1968, deep within the laboratories of 3M, a company already renowned for its commitment to fostering innovation. Spencer Silver, a diligent senior chemist, was engaged in a project with a clear, ambitious objective: to develop a “super-strong adhesive” specifically engineered for demanding applications within the aerospace industry. However, in a classic twist of scientific serendipity, Silver’s experiment did not yield the anticipated result. Instead of a powerful, permanent bond, he “accidentally created a ‘low-tack’, reusable, pressure-sensitive adhesive”.

Silver himself described this unexpected outcome as “quite astonishing”. He had stumbled upon an unusual combination of “high tack” – meaning the adhesive felt sticky to the touch – with “low peel adhesion,” which allowed it to be easily removed from a surface without causing damage. He famously likened its unique stickiness to “sticking to a bunch of marbles,” vividly illustrating its peculiar properties. The adhesive’s distinctiveness lay in its composition: tiny, indestructible acrylic microspheres. These spheres allowed the adhesive to stick only where they were tangent to a surface, providing just enough grip to hold papers together while simultaneously being weak enough to permit easy removal without tearing the underlying material. Crucially, this adhesive could be used repeatedly. Despite these intriguing properties, Silver’s invention was initially deemed a “solution without a problem”. At the time, 3M’s research focus was almost exclusively on developing stronger, more permanent adhesives, making Silver’s discovery appear to be a deviation or even a failure in the context of his original assignment.

For an arduous five years, Silver passionately championed his discovery within 3M. He promoted it through informal discussions and formal seminars, earning him the nickname “Mr. Persistent” due to his unwavering belief in the adhesive’s latent potential. However, he “failed to gain adherents” or find a viable commercial application for his novel adhesive. Early attempts to devise a marketable product, such as a spray adhesive or a coated bulletin board designed for temporary notices, proved commercially unsuccessful. The bulletin board, for instance, failed partly because its surface collected dust, highlighting the practical challenges of applying the novel adhesive in a commercially viable way.

The prolonged incubation period of Spencer Silver’s adhesive, explicitly labeled a “solution without a problem” for 5-6 years within 3M, stands as a direct reflection of 3M’s distinctive corporate innovation culture. This retention of a seemingly “failed” or “useless” invention, rather than its immediate discard, was made possible by the company’s “15% Culture”. This policy encourages employees to dedicate a portion of their work time to pursuing innovative ideas that excite them, even if those ideas do not have immediate commercial applications. This culture was deeply rooted in the philosophy of former 3M President and Chairman of the Board, William L. McKnight, who famously advocated: “Hire good people and leave them alone. Delegate responsibility and encourage men and women to exercise their initiative. Management that is destructively critical when mistakes are made kills initiative. And it’s essential that we have many people with initiative if we are to continue to grow“. This environment fostered a profound tolerance for experimentation and promoted a long-term vision for research and development, allowing novel ideas to incubate without the intense pressure of immediate commercial viability.

The Post-it Note story thus becomes a pivotal case study for how organizational culture directly impacts innovation. It demonstrates that true, disruptive innovation often requires patience, a willingness to invest in seemingly unproductive research, and a leadership structure that empowers employees to champion their discoveries, even when initial market or internal assessments are pessimistic. This approach stands in stark contrast to companies that might prematurely abandon projects without immediate, tangible return on investment, thereby potentially stifling future breakthroughs.

The Eureka Moment: Art Fry’s Hymnal Revelation

The critical turning point for Spencer Silver’s adhesive arrived in 1974, when Art Fry, a fellow 3M scientist and product development specialist with a background in chemical engineering, happened to attend one of Silver’s seminars. Fry, who regularly sang in his church choir, was grappling with a persistent, albeit minor, personal frustration: the paper bookmarks he used to mark hymns in his hymnal repeatedly fell out, and traditional adhesives, if used, would damage the delicate pages.

During a particularly “boring sermon,” Fry experienced what he later described as a “eureka head-flapping moment”. He suddenly realized that Silver’s unique, reusable adhesive, which he had learned about in the seminar, could provide the perfect temporary anchoring solution for his bookmarks. This was the critical juncture where Silver’s “solution” finally encountered a relatable, everyday “problem,” unlocking its latent potential.

Inspired by this realization, Fry immediately began creating sample bookmarks by coating small pieces of paper with Silver’s adhesive. He was able to pursue this idea by leveraging 3M’s progressive “permitted bootlegging” policy, which formally allowed employees to dedicate a portion of their work time to pursuing projects of their own choosing, fostering an entrepreneurial spirit within the company. A charming detail of the Post-it Note’s origin is the choice of its iconic canary yellow color. This was not a result of extensive market research or strategic branding; it was chosen purely “by chance,” as it was the color of scrap paper readily available in the lab next door to Fry’s team.

Fry’s initial use of these clever bookmarks quickly expanded beyond his hymnal. He began using them to exchange notes with his supervisor, and the product’s immediate communicative effectiveness became apparent within the office environment. Prototypes rapidly gained traction within 3M’s corporate headquarters, where employees enthusiastically adopted them for internal messaging, quickly becoming “hooked” on their convenience and versatility. Fry quickly grasped the broader implications of his discovery, articulating his vision: “I thought, what we have here isn’t just a bookmark. It’s a whole new way to communicate“.

The pivotal connection between Art Fry’s personal frustration with slipping bookmarks and Spencer Silver’s dormant adhesive was not merely a stroke of individual brilliance; it was fundamentally enabled by 3M’s organizational environment. The existence of 3M’s “15% Culture” and “permitted bootlegging” policy was paramount. These policies created an internal ecosystem where knowledge sharing, such as Silver’s seminars, was actively encouraged, and employees like Fry were granted the autonomy and dedicated time to pursue unconventional ideas that resonated with their personal experiences, even if these ideas fell outside their immediate job descriptions. This fostered a fertile ground where seemingly disparate discoveries could “collide” and find unexpected purpose. This case vividly illustrates that fostering innovation requires more than just hiring talented individuals; it demands a deliberate, flexible, and empowering corporate culture. An organization must provide the channels for cross-pollination of ideas and the freedom for employees to experiment and explore. This underscores that true innovation is often a collaborative and iterative process, where personal insights, combined with robust organizational support, can transform a “solution without a problem” into a universally valued product.

From Skepticism to Success: The Rocky Road to Market

Despite the burgeoning internal enthusiasm for Post-it Notes, the path to market was far from smooth. Management, having been “burned” by the previous commercial failure of the Post-it bulletin board, remained highly skeptical of this new product. The product faced significant technical hurdles in its development, requiring several more years to perfect its design and manufacturing processes. A key challenge was ensuring the adhesive would consistently stick to the paper without peeling off when the note was removed from another surface—a seemingly simple but crucial detail for user satisfaction. To overcome this, two additional 3M scientists, Roger Merrill and Henry Courtney, were brought in. Their critical contribution was inventing a special coating for the paper that effectively held the adhesive in place, making the Post-it Note viable for mass production.

In 1977, after years of development, 3M cautiously test marketed the product in four cities under the name “Press ‘n Peel”. The results were profoundly “disappointing” and “lackluster”. Consumers “didn’t quite know how to use it” or grasp its utility, leading to minimal sales. This initial failure appeared to validate management’s long-held skepticism about the product’s viability.

Refusing to be deterred, Geoff Nicholson (Fry’s boss) and Joe Ramey, key internal champions, believed the problem wasn’t the product itself, but the way it was marketed. A year after the “Press ‘n Peel” flop, in 1978, they launched a decisive “massive marketing campaign” known as the “Boise Blitz”. This campaign strategically involved renaming the product to “Post-it Note” and, crucially, giving out large quantities of free samples directly to offices in Boise, Idaho. The goal was to put the product directly into consumers’ hands, allowing them to experience its utility firsthand. The results were overwhelmingly “promising” and a “runaway success”. More than 90 percent, and in some accounts, even 95% of those who received samples indicated they would buy the product, proving the concept’s immense potential.

Buoyed by the undeniable success of the Boise Blitz, Post-it Notes were officially launched across the United States in 1980, making their debut in US stores on April 6, 1980. Once in the hands of consumers, the notes “spread like a virus” and quickly became an “overnight success”. As Spencer Silver noted, it was a product “nobody thought they needed until they did”. The following year, the Post-it Note’s global expansion began, with launches in Canada and Europe in 1981.

The dramatic difference in outcomes between the failed “Press ‘n Peel” launch and the overwhelmingly successful “Boise Blitz” reveals a critical principle for marketing truly novel products. The initial launch failed because consumers could not immediately grasp the product’s utility. In contrast, the “Boise Blitz” succeeded by providing free samples and enabling direct user experience. This demonstrates that for products that are genuinely innovative or introduce a new way of doing things, where the value is not immediately obvious from traditional advertising, direct, hands-on experience – a form of experiential marketing – is indispensable. It allows consumers to discover the “aha!” moment for themselves, transforming initial skepticism into immediate appreciation. The Post-it Note, once its utility was understood through use, became a “self-advertising product” , as recipients of documents with notes attached would become curious and seek them out. This highlights a fundamental marketing principle: sometimes, the most effective way to sell a disruptive innovation is to let the product speak for itself through user interaction. It underscores that initial market failure is not necessarily a product flaw, but often a signal to rethink the marketing approach, shifting from mere information dissemination to immersive, value-demonstrating strategies. This lesson remains particularly relevant for startups and established brands introducing genuinely novel concepts to the market.

To provide a clear overview of the journey, the key milestones in the early history of the Post-it Note are summarized below:

Post-it Note Key Milestones (1968-1980)

Sticking Around: Evolution and Diversification of the Post-it Brand

What began as a single, small yellow square has undergone a remarkable diversification, evolving into a vast product line that now commands its own dedicated aisle in office supply stores globally. Post-it Notes are now available in an extensive array of “various colors, shapes, sizes and adhesive strengths,” catering to a multitude of preferences and uses. There are at least 28 documented colors of Post-it Notes as of 2024, alongside various shapes and sizes ranging from mini (1.5 x 2 inches) to full-page (8.5 x 11 inches). Different colors are often associated with specific purposes, such as classic yellow for general notes, vibrant pink for urgent tasks, or calming blue for regular reminders.

The brand’s expansion has also seen the introduction of several specialized product lines over the years:

- Post-it Flags: These were introduced as a new way to organize with color coding, filing, and indexing, offering a more precise method for referencing specific sections in documents and books.

- Post-it Easel Pads: Introduced in 1995, with versions for kids following in 1996, these large, self-sticking pads revolutionized brainstorming and presentations, allowing ideas to be easily captured, displayed, and rearranged on walls or easels.

- Post-it Brand Super Sticky Notes: Recognizing a need for stronger adhesion on vertical or non-smooth surfaces, these notes with a stronger glue were introduced in 2003.

- Post-it Super Sticky Dry Erase Surface: In 2014, 3M released this innovative product, an instant, stain-free dry erase surface that can be customized to fit various spaces like walls, cabinets, and desks, further extending the brand’s reach into collaborative tools.

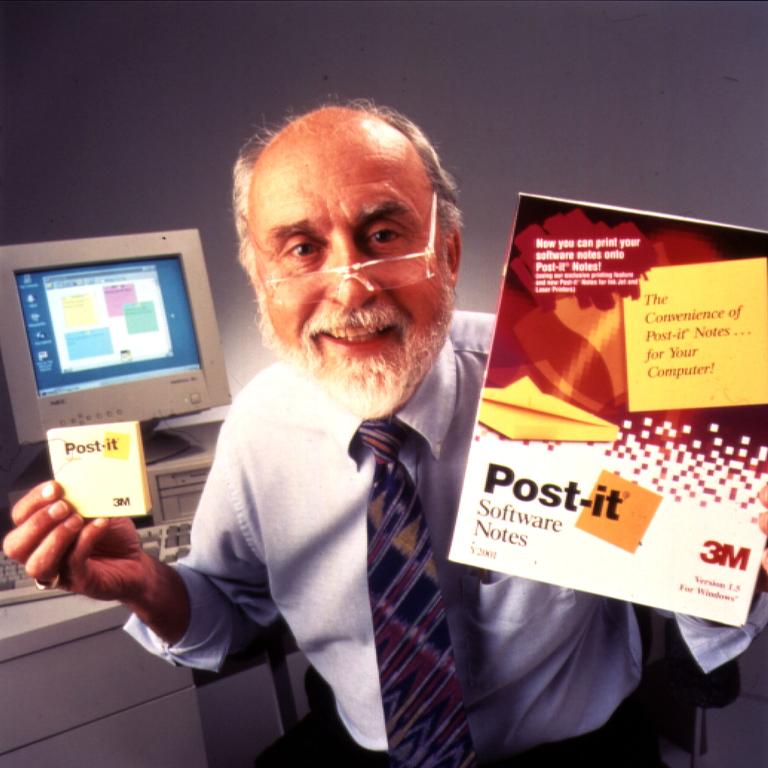

Beyond physical products, the Post-it brand has successfully adapted to the digital age. The Post-it app, which was awarded ‘Best of’ App of 2019 by Google Play, allows users to capture, organize, and share their physical Post-it Notes digitally. Digital versions of Post-it Notes are also integrated into popular software like Microsoft Teams and Google Workspace. Notably, a temporary conflict between 3M and Microsoft over the creation of electronic Post-its in Office 97 eventually led to a collaboration in 2004, which firmly established the Post-it brand within the Windows ecosystem. This strategic move ensured the brand’s relevance in an increasingly digital world, bridging the gap between tactile and digital organization.

Despite the expiration of 3M’s patent on the original adhesive in 1997, the “Post-it” brand name and the original notes’ distinctive canary yellow color remain registered company trademarks. This strong brand identity has allowed 3M to maintain its market leadership, with competitors often using generic terms like “repositionable notes” for similar offerings.

Beyond the Desk: Cultural Impact and Enduring Relevance

The Post-it Note quickly transcended its humble origins to become a profound cultural artifact, transforming communication and organization across various spheres of life. It became synonymous with quick notes, efficient reminders, and streamlined organization. Their visual nature makes them excellent tools for organizing thoughts, tasks, and ideas, allowing users to categorize tasks by urgency or project type using different colors, thereby creating an easily understandable visual map of their workload.

In the professional realm, Post-it Notes have profoundly impacted office culture. They are invaluable in collaborative settings, allowing team members to jot down ideas, questions, or feedback and affix them to shared boards or walls. This method encourages open communication and ensures that all voices are heard during brainstorming sessions. The ease with which Post-its can be rearranged makes them perfect for grouping ideas, developing project plans, or creating workflow charts in real-time. Their disposable nature fosters a sense of freedom in brainstorming, encouraging iteration and exploration of ideas without the pressure of permanence. The limited size of a Post-it Note also forces concise thoughts, leading to more focused conversations and quicker pivots in idea generation. Furthermore, their use democratizes participation in group activities, giving everyone a voice and valuing all contributions equally, which can be particularly beneficial for shy or less vocal individuals.

The impact of Post-it Notes extends significantly into education, where they serve as a terrific low-tech teaching tool. Educators utilize them for a wide array of pedagogical purposes:

- Curing Writer’s Block: Students can brainstorm ideas on individual notes, which can then be grouped and sequenced to form an outline.Poster Session Peer Review: Students can leave comments or questions on peers’ research posters using Post-it Notes, facilitating feedback for revision or engagement tracking.

- Visual Check for Understanding: Teachers can gauge class comprehension by having students place notes on a “confident” to “confused” spectrum on the board, sometimes even quantifying their understanding.

- Interactive Learning: They are used for activities like identifying key moments in readings, storyboarding writing, or labeling items in a target language.

- Motivation and Feedback: Teachers use them for “way-to-go!” recognitions, extra credit points, or even as a visual disciplinary measure.

At home, Post-it Notes are equally effective for personal organization and creative endeavors. They serve as quick and visible reminders for tasks, deadlines, or appointments, easily affixed to computer monitors, desks, or mirrors. Their flexibility allows for easy rearrangement, prioritization, or discarding of tasks. The “Post-it Note decluttering method,” for instance, uses different colored notes (e.g., green for keep, orange for maybe, pink for get rid) to visually sort items like clothes, simplifying decision-making and reducing mental effort. Beyond utility, Post-it Notes inspire creativity: they can be used to create pixelated art on walls, color-code family notes, label tangled cables, or even serve as a dust catcher when drilling. They are also popular for solo brainstorming, temporary mind mapping, and setting visual goals.

In a world increasingly dominated by digital tools, Post-it Notes have remarkably maintained their relevance and enduring appeal. This persistence is attributed to their uniquely tactile nature; there is an undeniable satisfaction in physically peeling off a note and sticking it where it can be seen—a tangible reminder, a physical message, or an idea in concrete form. This aligns with a growing desire among consumers to “switch off” from excessive screen time and digital distractions, seeking offline experiences that are both beautiful and tactile. The continued success of Post-it Notes underscores that while digital solutions offer convenience, the simple, physical act of writing and placing a note fulfills a fundamental human need for direct, visual, and easily manipulable communication and organization.

Legal Landscape and Recognition

The immense success and ubiquitous presence of Post-it Notes inevitably led to challenges and recognition within the legal and innovation landscapes.

One notable challenge came from competing claims of invention. Alan Amron claimed to have been the actual inventor of the sticky note in 1973, a year before Art Fry’s “eureka moment”. Amron alleged he had conceived the idea for a “Press-on Memo” after using chewed gum to stick a note on his fridge. He filed a lawsuit against 3M in 1997, which resulted in a confidential settlement. As part of this settlement, Amron agreed not to make future claims against the company unless the agreement was breached. However, in 2016, he launched a further suit against 3M, seeking $400 million in damages and asserting that 3M was wrongly claiming to be the inventor, thereby breaching the previous agreement. A federal judge dismissed this suit, upholding the 1998 settlement. It is important to note that Amron never patented his invention, whereas 3M held the patent over the adhesive that made the sticky note commercially viable.

Beyond claims of origin, 3M also engaged in trademark disputes to protect its iconic brand. In 1997, 3M sued Microsoft for trademark infringement when Microsoft’s Office 97 software included an electronic sticky note feature using the term “Post-it” in a help file. This conflict eventually evolved into a collaboration, with the companies announcing in 2004 a partnership that established the Post-it brand more firmly within the Windows operating system. This demonstrates 3M’s proactive approach to defending its intellectual property, particularly the “Post-it” brand name and the distinctive canary yellow color, which remain registered company trademarks even after the adhesive patent expired in 1997.

The widespread success and innovative nature of the Post-it Note have also garnered significant recognition and awards for its creators and the company. The Post-it Note team received the internal 3M Golden Step Award in both 1981 and 1982, acknowledging the product’s substantial new sales and lucrative nature. Additionally, they were honored with 3M’s Outstanding New Product Award in 1981. In 2010, both Spencer Silver and Art Fry, the co-creators of the Post-it Note, were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, a testament to the product’s widespread success and impact. More recently, in 2019, the Post-it app itself received recognition, being awarded ‘Best of’ App of 2019 by Google Play, highlighting the brand’s continued innovation and relevance in the digital sphere.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Serendipity, Persistence, and Human Connection

The brand story of Post-it Notes is a compelling testament to the unpredictable nature of innovation and the power of human ingenuity and perseverance. What began as an accidental discovery—Spencer Silver’s “solution without a problem” adhesive in 1968—was patiently nurtured within 3M’s unique innovation culture, particularly its “15% Culture.” This environment allowed a seemingly failed experiment to incubate for years, demonstrating a corporate foresight that valued potential over immediate application.

The pivotal moment arrived with Art Fry’s personal frustration, which serendipitously connected with Silver’s dormant invention, leading to the “eureka moment” of the repositionable sticky note. This collaboration, fostered by 3M’s supportive policies, transformed a personal inconvenience into a universal solution. The journey from internal prototype to global phenomenon was not without its challenges, including an initial failed market launch. However, the determination of internal champions and a strategic shift to experiential marketing, exemplified by the “Boise Blitz,” proved that direct user experience was crucial for a product whose value needed to be discovered through use.

Today, the Post-it Note brand has evolved far beyond its original yellow square, diversifying into a vast array of sizes, colors, and specialized products, while successfully adapting to the digital landscape with its popular app and software integrations. Yet, its enduring appeal in a digital age lies in its uniquely tactile nature, offering a simple, physical means of communication and organization that resonates with a fundamental human need.

The Post-it Note is more than just a stationery product; it represents the beauty of simplicity, the power of persistence, and the profound impact of collaborative problem-solving. Its story underscores that transformative innovations often emerge from unexpected places, requiring not just brilliant minds, but also an organizational culture that embraces experimentation, tolerates initial setbacks, and champions ideas until they find their true purpose. It stands as a powerful symbol of how a humble, accidental invention can, through a blend of scientific discovery, individual insight, corporate support, and effective market introduction, fundamentally change the way people work, learn, and live, leaving an indelible mark on global culture.

To read more content like this, explore The Brand Hopper

Subscribe to our newsletter