By the 1990s, Guinness was a well-known global stout brand, but it faced new challenges: stout was seen as heavy and time-consuming to pour, especially compared to quick-pouring lagers. In fact, market research had found many consumers viewed the famous 119.5-second pour as a drawback. Andy Fennell (Guinness marketing director, 1997–2001) later recalled that the brand’s performance had become “lacking somewhat” under prior campaigns. Historically, Guinness had a heritage of memorable advertising (from “Guinness is Good for You” to clever toucan posters), but by the late 1990s, it needed a breakthrough to reinvigorate its premium positioning.

Strategic Objectives and Positioning

In 1996, Diageo (Guinness’s owner) briefed agencies simply “to get the brand growing faster,”. AMV BBDO won the account in a dramatic pitch that fully acknowledged Guinness’s long pour time and proposed turning it into an asset. The agency identified the extended pour as a core “product truth” and coined the now-famous line “Good things come to those who wait” to capture it.

In other words, Guinness would own the narrative of patience and reward. This tagline deliberately reframed a perceived weakness as a unique virtue. The strategic aim was to reinforce Guinness’s premium, almost ritualistic image: if the wait makes the beer better, then pouring slowly becomes part of the experience. As one analyst noted, this approach exploits the psychology of delayed gratification by suggesting that “one great wave [or pour] is better than being out all day taking a lot of mediocre waves.”

Creative Concept and Execution

The creative execution unfolded through a series of cinematic ads, each dramatizing patience in a different narrative. Importantly, AMV treated the strict UK alcohol ad rules (no overt sports heroics or claims) as a playful challenge.

For example, the first ad, “Swimblack” (1998), features an aging local swimmer racing from a buoy to a pub against the clock of a Guinness being poured. Viewers learn that the swimmer’s brother deliberately “starts the clock” late so the hero never loses. This warm story (set in Monopoli, Italy) literally turns the 119.5‑second pour into a heartwarming race, making the delay part of the punchline.

Print and billboard ads reinforced the theme with similar imagery and copy. The campaign quickly proved successful with its target – older males – and was praised by the industry: “Swimblack” won a Creative Circle Gold for Best Editing and a Gold at the British Television Awards. Guinness’s management even credited the ad with around a 12% sales uplift in its launch period, justifying further investment.

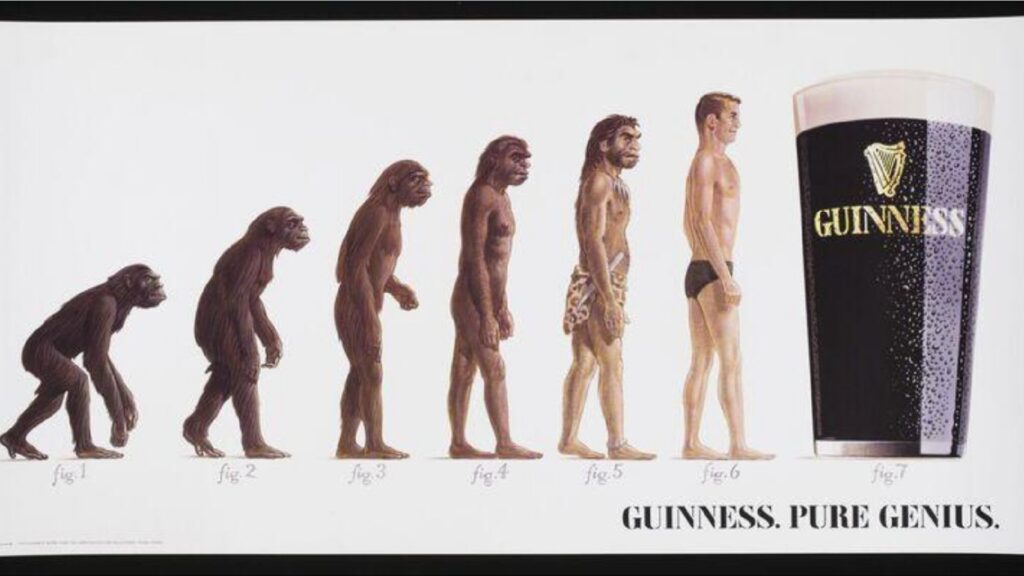

Following Swimblack, AMV rolled out “Surfer” (1999), a 60-second black-and-white epic often cited as one of advertising’s masterpieces. In this ad a band of surfers waits for “the perfect wave.” The long, tense build-up ends with a ferocious breaker that transforms into a stampede of crashing white horses. (This striking visual was inspired by Walter Crane’s painting Neptune’s Horses and an evocative nod to Moby Dick.) Only one surfer conquers the ultimate wave; as he celebrates on shore, the narration (a dramatic male voice) toasts viewers’ dreams. The implicit message is clear: just as a single perfect wave is worth waiting for, so is the perfect pint of Guinness.

Surfer’s high production values were extraordinary (shot in Hawaii over nine days) and its intense Leftfield soundtrack heightened the emotional impact. The result was both a critical and cultural sensation – the ad “dominated the 1999 awards season, winning more accolades than any other commercial that year” (Clio Lions, D&AD Pencils, Cannes Lions, etc.). In a 2000 poll by Channel 4 and The Sunday Times, “Surfer” was voted the all-time greatest TV ad in Britain, cementing its legend.

The campaign continued with “Bet on Black” (2000), also known as the Snail Race ad. Returning to a colorful style like Swimblack, it depicts a town’s comical snail race – slow at first, but then the snails rocket forward in a burst of speed (coinciding with a refreshing pull of Guinness). The winning snail named Black is carried off amid celebration with a pint. This spot playfully equates waiting and betting on Black the snail with the payoff of the stout. Directed by Frank Budgen (who also did Dreamer), Bet on Black was another creative hit: it earned a Cannes Silver Lion and UK TV Ad Awards Silver. A fourth ad, “Dreamer” (2000), returned to Surfer’s black-and-white motif (a man dreams of surfing while listening to samba), but it was the first three ads that became the iconic core of the “Good things…” campaign.

Taken together, these ads dramatised the patient pursuit of a reward in different ways (swimming race, surfing, snail racing) and linked it all to Guinness.

Media Strategy and Channel Selection

Guinness backed the creative campaign with broad media support. The centerpiece ads were long-form TV and cinema spots (typically 60–90 seconds) to capture viewers’ full attention, as seen in Swimblack, Surfer, and Bet on Black. High-impact prime-time TV slots and movie-theater screenings were used to showcase the cinematic visuals.

Print and outdoor ads (billboards and posters) also ran concurrently, featuring stills and taglines from the campaign to reinforce the message. Even without digital media (this was pre‑social-media), Guinness used festivals and in-pub activations (such as a live “Guinness Gastropod Championship” snail race in London tied to Bet on Black) to engage the target audience. In later years, the brand continued this immersive approach: for example, the 2007 Tipping Point ad was supported by an early transmedia campaign (“La Fiesta de Toppling”) with an online puzzle game.

Overall, the multi-channel mix ensured the campaign’s striking stories reached a wide audience across Britain.

Consumer Psychology and Cultural Resonance

The campaign deliberately harnessed deep psychological ideas. By reframing Guinness’s lengthy pour as part of a ritual, it tapped into the joy of delayed gratification. Behavioral science commentators note that this plays on a basic insight: waiting can heighten anticipation, making the final reward seem even more satisfying. This was made explicit in the Surfer ad: “If you see the right wave, one great wave is better than being out all day taking a lot of mediocre waves,” as one ad analyst put it. The soothing yet intense narration in Surfer (“Here’s to your dream”) further elevated the emotional tone.

Guinness also wove cultural references into the ads to give them mythic weight. The black-and-white cinematography of Surfer, and its use of Walter Crane’s Neptune’s Horses and Moby Dick imagery, gave the spot an almost artistic grandeur. Likewise, Swimblack’s Mediterranean village scene and affectionate brotherly twist resonated with a sense of community tradition. The slogan itself – a common proverb – had wide appeal and even cultural resonance beyond beer. As one creative said of Surfer: it was “a product truth dramatized in a really surprising way,” harking back to an era when ads aspired to be as entertaining as the TV programmes around them. Indeed, years later audiences remembered the ads vividly.

A 2018 survey found that 48% of people (72% of ages 35–54) still recalled the Surfer ad, and 25% ranked it the best commercial of the 1990s. This enduring recall shows the campaign’s deep psychological and cultural impact.

Competitive Landscape

In the late 1990s and 2000s, Guinness operated in a fiercely competitive beer market. U.S. and European imports (Heineken, Budweiser, etc.) and domestic lagers (Carling, Fosters, Stella) dominated shelf space and advertising budgets.

Unlike many lagers, Guinness could not sell on speed of service or lightness; it had to own its niche. Moreover, British alcohol-ad rules prohibited showing active sports or unattainable feats. AMV skillfully “bent” these rules: Swimblack and Bet on Black feature sporting contests (swimming, racing), and Surfer shows a life-threatening feat, but all were framed in friendly or symbolic ways that passed regulations.

The result was that Guinness stood out from competitors: instead of pitting a hero against another hero, it put ordinary people (aging swimmer, beach surfers, a snail race crowd) at the center of epic moments. This made the brand feel more relatable and human. In subsequent years Guinness continued to face shifts in tastes (e.g. rise of craft beers, cider, and low-alcohol drinks), but the “Good things” campaign had already refreshed its image. (For example, by 2013 Guinness still leaned on its iconic assets – “Good Things” and Surfer – even as it sought younger drinkers.)

Reception and Industry Response

The campaign’s reception was overwhelmingly positive among both the public and the industry. Critics and trade publications hailed Surfer in particular. It “exploded” out of Cannes to achieve cult status, and it “won more awards and generated more column inches than any other ad ever,” as its creative director later boasted. Advertising juries agreed: Surfer swept top honors (Clio, Cannes, D&AD) in 1999. In 2000 it was voted the best UK TV ad of all time by a Sunday Times/Channel 4 poll, and it still ranks highly in retrospective “greatest ads” lists. Swimblack and Bet on Black earned awards too (for editing, direction, etc.), helping Guinness win AdWeek’s coveted “Advertiser of the Year” Clio trophy in 2001.

Public response was similarly enthusiastic. The striking imagery and storylines made each ad a talking point in pubs and living rooms. Decades later, Surfer remained memorable – in 2018 one study found it had 48% unaided recall, far above typical rates. Similarly, Swimblack became an instant classic in ad circles: it was quickly judged among Britain’s finest TV commercials of the era. By contrast, typical beer ads of the 1990s rarely elicited such a strong cultural footprint.

Measurable Impact on Brand Performance

The practical impact on Guinness’s business was significant.

According to AMV, Swimblack alone delivered about a 12% increase in sales volume, exceeding internal targets. (This boost was helped by other factors like the simultaneous launch of Guinness Extra Cold, but managers credited the campaign’s momentum.)

With Guinness now viewed as more exciting and relevant, sales and market share rebounded through the early 2000s. By comparison, competitors without a standout message often saw only incremental gains.

Over the long term, Guinness’s careful brand-building paid off: global net sales of Guinness grew steadily. By 2022, Guinness was named “Britain’s Favourite Pint” and achieved a 22% year‑on‑year sales jump in the UK and Ireland.

Remarkably, by 2023 Guinness had become the UK’s best-selling draft beer, with roughly 11% share of the market.

These results reflect not only ongoing marketing efforts but the enduring equity created by the “Good Things” campaign. In other words, a message built around patience helped drive immediate sales gains and also strengthened the brand for decades.

Global Adaptations and Local Campaigns

While the UK ads leaned on the waiting motif, Guinness used different themes abroad. The “Good Things” line proved hard to translate culturally, so Diageo developed local campaigns.

In Africa (especially Nigeria, Ghana, etc.), the company launched the Michael Power series (1999–2006). Michael Power, a James-Bond-like African hero, embodied the slogan “Guinness gives you power,” leveraging local narratives of ambition and strength. This campaign made Guinness the continent’s top imported beer by portraying aspirational masculinity tailored to African audiences.

In Southeast Asia, a similar concept ran as the Adam King campaign starting in 2002. Adam King, like Michael Power, was a dashing globetrotter; by 2004 this effort had vaulted Guinness into the top three beers in markets such as Singapore and Malaysia (20% regional share). In China and other markets, Guinness has used sport and social occasions to connect (e.g. sponsoring rugby, Premier League).

In all cases, the core lesson was that Guinness brand values (greatness, surprise, quality) could be told in many ways: the UK ads emphasized ritual and patience, Africa focused on empowerment, Asia on personal achievement, etc. This localization proved wise: in Africa “Guinness” became synonymous with success and leisure, while in Asia the hero ads gave the brand aspirational cachet.

Legacy and Long-term Brand Strategy

The “Good Things Come to Those Who Wait” campaign has had a lasting legacy for Guinness. Its emphasis on storytelling and the payoff of patience has become part of Guinness’s DNA. Decades later, the company still revives this theme when fitting. For instance, in 2021 Guinness ran a nostalgic ad (#LooksLikeGuinness) that explicitly recycled the slogan to capture the world’s collective longing for pubs after COVID lockdowns.

In that commercial, everyday scenes that “look like” Guinness (a cat, laundry on a line) culminate in friends finally raising real pints – under the tagline “Good things… come to those who wait”. The fact that Guinness can re-use the phrase in 2025 and it still resonates shows how strong the campaign imprint was. More broadly, the campaign set a precedent for Guinness to position itself through cinematic artifice; later ads like Tipping Point (2007) and Arthurs Day events (2009) built on this creative pedigree. Today Guinness remains a top-selling stout worldwide, and its marketing continues to emphasize the brand’s heritage of quality, storytelling, and even virility (the legacy of Michael Power).

Key Takeaways for Marketers

-

Turn a weakness into a strength. Guinness famously leveraged its 119.5‑second pour – originally a consumer complaint – as the core of its message. By honestly acknowledging a “flaw,” the ads built trust and set Guinness apart. This is an example of the “pratfall effect”: acknowledging a vulnerability can make a brand more likable and memorable.

-

Focus on product truth and storytelling. The campaign succeeded because it identified one simple truth (the wait) and built rich narratives around it. Each ad was a short film, not just a sales pitch. Viewers loved the stories (heroic swimmer, surfers chasing waves, a snail race), which made Guinness feel more mythical and entertaining. The lesson is that consumers engage deeply with emotional stories tied to product realities.

-

Protect bold creative ideas. AMV BBDO trusted its gut even when initial testing was lukewarm; the agency “protected” Surfer until launch, ignoring negative research and refusing to dilute the vision. Marketers should note that disruptive ideas often defy conventional metrics; deep conviction (and a track record like Swimblack’s 12% lift) can justify the risk of a grand creative bet.

-

Use integrated channels and events. Guinness supported the TV ads with print, outdoor, and experiential PR (like live snail races) to create a unified campaign. Moreover, later campaigns (e.g. Tipping Point) illustrated how digital challenges and branded content can extend reach. The integrated approach ensured the brand’s narrative was omnipresent.

-

Adapt to local culture. What worked in Britain would not directly work everywhere, so Guinness developed tailored campaigns (Michael Power in Africa, Adam King in Asia) to reflect local aspirations. The key is that while the global brand promise (“greatness” or “quality”) stays the same, the execution must speak to regional values and symbols.

-

Build long-term equity. Finally, Guinness’s case shows the value of consistency over years. The “Good Things” platform remained part of brand lore for decades and could be revived for new contexts (e.g. post-lockdown). Marketers should aim to create campaigns that contribute enduring brand meanings, not just short-term promotion. Indeed, Guinness eventually became Britain’s favorite pint and the UK’s top draft beer – achievements partially attributed to this rich legacy of advertising.

-

Also Read: A Case Study on Absolut Vodka’s “Absolut Bottle” Campaign

To read more content like this, subscribe to our newsletter